After measles outbreak, interest in vaccines increases

on March 20, 2015

It’s not over yet.

The measles outbreak, which started in December, 2014, at a Disneyland theme park in Orange County, is still ongoing in the United States, and has now reached Mexico and Canada, where more than 100 people have been reported to have the disease.

By March 6, 17 US states and the District of Columbia reported measles cases, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) website. The CDC is only one of the many health entities that periodically update the outbreak’s numbers, and delivers to the community the same message: Measles, which is highly contagious, is also highly preventable through vaccination. Most of the people infected weren’t immunized, according to CDC’s website.

Even though there isn’t any data yet to measure how the recent measles outbreak has affected local vaccination rates, health officials from Alameda or Contra Costa counties agree that “anecdotally,” more parents seem to be worried about the disease and eager to know more about the vaccine.

“It is too soon to know how the current measles outbreak has impacted the immunization rates,” Dr. Gil Chavez, deputy director and state epidemiologist at the California Department of Public Health (CDPH), wrote in an email. “However,” he added, “the outbreak has caused people to be more aware of measles and has been associated with widespread awareness of the importance of high vaccination rates for preventing measles spread.”

Chavez said that any changes in immunization as a result of the current outbreak would be reflected in data collected in the fall of 2015.

Alameda County accounts for six of the 133 measles cases in California, according to data updated by the CDC on March 13. Pediatrician Erica Pan, director of the division of communicable diseases at the Alameda County Department of Pubic Health (ACDPH), also said that it was too early to have data, but that anecdotally she could see how the outbreak was affecting the community. Pan said that more parents are calling the health department to ask about measles and vaccines. And when that happens, she adopts the same position: As a fellow parent, a pediatrician and a public health official, she tells them that vaccines are “safe and effective.”

Pan also reminds worried parents that measles can be deadly–in the hospital, 1 in 1,000 patients with measles die from brain infection, a complication of the disease. “It can be really devastating,” she said.

The parents who are calling about vaccines don’t seem to be those who oppose vaccination, but those who are “on the fence,” said Pan—parents who are not really sure about vaccines, but are not part of the so-called “anti-vaccination movement.” Some parents oppose vaccination due to safety concerns, or because they question the effectiveness and necessity of vaccines.

Something similar is occurring in neighboring Contra Costa County, where there are no numbers yet measuring a change in vaccination rates, but there have been more calls to the county health department. “We have received calls from parents, schools, schools’ nurses, childcare providers, even health care providers, physicians and nurses about measles vaccines,” said Paul Leung, immunization coordinator at Contra Costa Health Services. Leung added that the department has provided information to each of these groups “about the importance of vaccination,” because “measles is very contagious.”

“We are all very interconnected and these diseases can spread across a wide area quickly,” Leung said. So far, only one measles case has been reported in Contra Costa County, according to CDPH’s data.

The health department has made available online several materials regarding vaccination, including a list of actions that parents, schools and healthcare providers can take to help the community stay protected. Its website also shows parents the county schools’ immunization levels through interactive maps that display data for childcare facilities and kindergartens.

Health officials said that one of the lessons learned from this ongoing outbreak is the importance of vaccination to increase community immunity. Because measles is airborne and very infectious, more than 90 percent of the population must be immune to control transmission, wrote state epidemiologist Chavez. That’s the idea of “herd immunity”—or that collective vaccination benefits those who can’t get immunized because they are younger than one year old, or are allergic to some component of the vaccine, or their immunize system is compromised because of certain condition, such as HIV. “Once the percentage of immune people decreases below this level, sustained outbreaks with ongoing transmission can occur,” he wrote.

“Another important lesson is that even when overall vaccination coverage is high, measles transmission can occur in smaller areas of groups with low coverage,” he added. It is still common to see localized spread in families or communities with persons who haven’t been immunized, he wrote, adding, “There are many different perspectives about measles vaccines, many of them inaccurate, available to parents.” He said that parents could find accurate information on the website Shotsforschool.org.

A new study published by a research team at Boston Children’s Hospital on March 16 in The Journal of the American Medical Association, Pediatrics links the Disneyland measles outbreak to inadequate vaccine rates. The report is based on epidemiological data and shows that immunization coverage among the exposed populations was far below the necessary percentage to create a herd immunity effect. For the people in California, Arizona and Illinois who contracted the disease after coming into contact with those originally infected at Disneyland, the immunization rate is between 50 and 86 percent, according to the study.

One of the roadblocks to herd immunity is that some families opt out of vaccinations required by schools by using personal belief exemptions, which parents fill out stating that they have decided not to vaccinate their children due to ideological reasons, not medical causes. According to the most recent data from the CDPH, over the past five years, the number of children with all required immunizations in all reporting schools in the state has decreased “very slightly” from 90.7 percent in the 2010-11 school year to 90.4 percent in the 2014-15 school year.

Health officials and experts have expressed concerns that lower rates of vaccination are due to an increase in the use of personal belief exceptions. In fact, a new law introduced in 2012, which went into effect last year, tried to require parents to talk to their health care provider before filling out the exemption. Even though this measure has its loopholes—naturopaths, who typically oppose vaccines, can also sign the exemptions, and religious exemptions were also allowed—vaccination rates began to show some changes. After the implementation of this law in California and a similar one in the state of Washington, the proportion of children with exemptions for personal beliefs has declined, according to Chavez.

Data available from the CDPH breaks the information about immunization into childcare (children ages 2 years to 4 years, 11 months), kindergarten and 7th grade. Data available through the National Immunization Survey breaks it into children, teens and adults groups.

According to the data about immunization levels available on CDPH’s website, the number of children with personal belief exemptions from the 2013-2014 school year to the 2014-2015 school year has decreased in most of the state’s counties, including Contra Costa and Alameda.

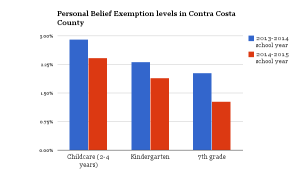

Personal Belief Exemption levels in Contra Costa County between 2013-2014 and 2014-2015, according to data from the California Department of Public Health.

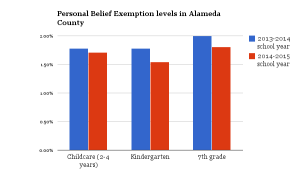

In total, 1.87 percent of children enrolled in childcare, kindergarten and 7th grade in Contra Costa County in 2014-2015 had personal belief exemptions; while in 2013-2014 the percentage had been 2.26. In Alameda County, 1.68 percent had personal belief exemptions in 2014-2015, and that percentage had been 1.82 in 2013-2014.

But some legislators and health officials don’t think that’s enough. In February, state Senator Richard Pan (D-Sacramento), a pediatrician who sponsored the 2012 bill, along with Senator Ben Allen (D-Santa Monica), and Assemblymember Lorena Gonzalez (D-San Diego), introduced Senate Bill 277. The bill aims to repeal personal belief exemptions in California, making it one of the 29 states that have introduced bills to make opting out of vaccines harder after the recent measles outbreak.

Personal Belief Exemption levels in Alameda County between 2013-2014 and 2014-2015, according to data from the California Department of Public Health.

In total, more than 70 vaccination bills have been introduced in 2015, according to data from the National Vaccine Information Center. The organization advocates against personal belief exemptions and for “the right of consumers to make educated, voluntary health care choices,” according to its website.

SB 277 will require that only children who have been vaccinated for various diseases, including measles and Pertussis (whopping cough), be admitted to a school in California. It would eliminate personal belief exemptions and only allows medical reasons for not vaccinating children.

The CDPH stated in a report that the percentage of kindergarteners with personal belief exemptions had “consistently increased annually among all reporting schools” until 2014-2015, when there was a 19 percent decrease in the percentage of kindergarteners with these exemptions compared with the previous year. In a press release, Senator Pan’s office described this as “dramatic” and “reversing a decade long trend.”

“By removing the ‘personal belief’ exemption in schools, SB 277 would guard against outbreaks while protecting every child’s right to go to school in a safe environment,” he wrote in an email. He added, “Since the outbreak, parents have been speaking up” and that “I hear every day from parents who are concerned that growing numbers of unvaccinated students are jeopardizing public health and putting their own children at risk unnecessarily.”

The bill has the backing of Catherine Martin, director of the California Immunization Coalition. “Our coalition has taken a support position on the bill and we hope is goes all the way to the governor’s office, and we hope he signs it,” she said. The group also supported the 2012 bill and has been providing technical assistance to write the recently introduced bill. Martin said that if it passes, the new bill would have “a really big impact,” especially on younger families and their decision-making regarding vaccines.

However, there’s a group of parents who are “very much against vaccines, period,” Martin said. She added that there’s another group of parents who take a more passive approach to vaccination and count on the rest of the community to be immunized. “I think those parents have seen that their decision could have negatively impacted their child,” Martin said.

Although the proposed bill eliminates every exemption that is not based on medical reasons, it is possible that religious exemptions could be reintroduced during the hearing process, which will begin in April. That’s what happened when Governor Jerry Brown signed the 2012 bill, which originally didn’t include religious exemptions, according to CDPH’s website.

“I think that’s a risk,” said Martin. However, she added that many policy makers—“hopefully including the governor”—have now seen what a break in herd immunity can do. “Not only it is a threat to the community and it can result in larger outbreaks,” she said, but there’s also a high cost to counties and schools that have to manage these outbreaks.

Erica Pan, from the Alameda County Department of Public Health, said she and the department support the idea of removing the personal belief exemptions. Contra Costa Health Services’ Paul Leung said that he wasn’t able to “comment on any sort of pending legislation,” but added “when the change in the personal belief exemptions became effective last year, we did see a decrease in our personal belief exemption level.”

SB 277 first hearing will be on April 8, and the Health, Education and Judiciary committees will oversee it.

Oakland North welcomes comments from our readers, but we ask users to keep all discussion civil and on-topic. Comments post automatically without review from our staff, but we reserve the right to delete material that is libelous, a personal attack, or spam. We request that commenters consistently use the same login name. Comments from the same user posted under multiple aliases may be deleted. Oakland North assumes no liability for comments posted to the site and no endorsement is implied; commenters are solely responsible for their own content.

Oakland North

Oakland North is an online news service produced by students at the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism and covering Oakland, California. Our goals are to improve local coverage, innovate with digital media, and listen to you–about the issues that concern you and the reporting you’d like to see in your community. Please send news tips to: oaklandnorthstaff@gmail.com.